In 1982, the National Distance Education Centre (NDEC) was first established at Dublin City University (DCU), then the National Institute of Higher Education Dublin (NIHED). This year marks the 40th anniversary of the launch of the National Centre following the recommendations of a high-level task force chaired by the Chief Executive of RTE, with representatives from industry, government departments, higher education and training agencies.

Mac Keogh (1998) reports that the Committee “encountered enthusiastic support for the distance learning approach in its discussions with various groups and recommended that a ‘Distance Education Unit’ should be set up in NIHED” (p. 3). Several pilot course offerings were proposed in Computing and Agriculture to test the viability of distance education in terms of demand and also the business model and collaborative networking approach. At the time, the stated objective was…

“To make educational qualifications available to the population irrespective of their geographic, social, economic or employment circumstances”.

Notably, Guinness gave a grant of £90,000 to help establish The National Centre and Apple Computer donated over £200,000 in equipment. This was a significant amount of financial support from industry partners back in 1982. Following the appointment of Dr Chris Curran as the foundation Director, and a handful of staff, the new Centre moved quickly and by October 1982, a course on Basic programming was launched. This course attracted over 2700 students living throughout Ireland.

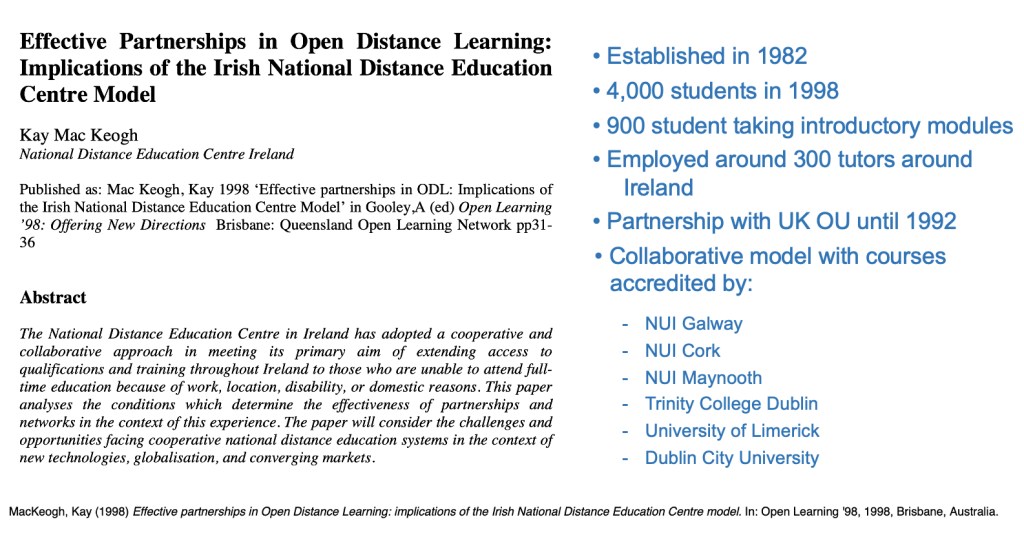

Importantly, the NCDE adopted a cooperative and collaborative approach to meeting its primary aim, with many partner higher education institutions across Ireland, including: NUI Galway, NUI Cork, NUI Maynooth, Trinity College Dublin and University of Limerick. Mac Keogh (1998) notes that…

“The cooperative structure of distance education was strengthened when the Minister for Education launched the National Distance Education Council in September 1985” (p. 5).

The Council’s role was consultative and sought to provide support and direction to the Centre in building a national distance education programme suited to national requirements. According to the Minister the objectives of Council were to:

- relieve growing pressure for places at third level;

- promote technological literacy;

- equalise opportunity for third level education;

- provide courses for adults in new skills and updating existing skills; and,

- give opportunity for lifelong learning.

The membership of Council included representatives from the universities, other educational institutions, research institutes, business, industry, training and trade unions. According to Mac Keogh (1998),

“During its existence the Council was vital in initiating and supporting a range of collaborative programmes” (p. 5).

By 1998, the core staff had grown to some eight academics, three administrators, 12 secretarial staff, a part-time staff of over 300 hundred located throughout Ireland, including subject leaders, tutors, course writers, editors, and study centre liaison officers (Mac Keogh, 1998).

In 1998, over 4000 students were enrolled on undergraduate, post-graduate and continuing professional education programmes in Information Technology, the Humanities, Nursing, Business, and Teacher Education. Over the years the National Centre evolved to become Oscail, with the President of Ireland, Mary McAleese, opening the National Centre for Distance Education building in 2001.

In 2014, Oscail then evolved to become DCU Connected with the Open Education Unit under the new National Institute for Digital Learning (NIDL) continuing to manage most of DCU’s fully online programmes. Over the past 40 years, thousands of students have graduated with university qualifications through DCU’s pioneering work in the field of online distance education. DCU is known as a world leader in digital education having hosted the 2019 ICDE World Conference on Online Learning.

Importantly, the National Centre’s original aim of expanding access to higher education, irrespective of social background, geographical location and economic circumstances, continues today, as evidenced by DCU’s commitment to access and its core mission of transforming lives and societies.

Beginning of a new chapter

DCU’s leadership in online, distance and digital education also continues today with a new chapter starting this year from September as all of the University’s online modules and programmes will be fully embedded into DCU’s five Faculties. This new faculty-led approach builds on the growing demand for online learning and DCU’s increased institutional capacity for digitally-enhanced models of education developed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. While this new development means there is no longer the need for a separate Open Education Unit, the considerable expertise developed over many years by this team has been distributed across faculties and other service units, with the NIDL continuing to provide overarching leadership.

DCU leads an important new national Initiative

DCU continues to play a national leadership role too, with the NIDL recently having been selected by Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) to help develop new National Statutory Quality Guidelines for Blended and Online Programmes. QQI is the state agency responsible for promoting the quality, integrity and reputation of Ireland’s further and higher education system.

This is an important new national initiative as following the COVID-19 pandemic we are seeing more institutions and education providers around the globe wanting to harness the flexibility that new technology-enhanced delivery models offer students. In announcing the NIDL’s role in leading this initiative, Walter Balfe, Head of Quality Assurance at QQI, with an extensive background in education and training, recently spoke about how these new statutory quality guidelines will help to ensure effectiveness and integrity for online learners.

“After living with COVID-19 restrictions, online became the primary medium for course delivery. The switch to online was rapid and forced, rather than being strategic. However, prior to the pandemic, QQI had created guidelines for providers seeking validation of blended learning programmes (those that combined face-to-face and online learning). Many providers took these guidelines on board to help deliver programmes and assessments online”, says Walter Balfe.

According to Walter, most Irish education providers generally adapted well to the new online way of teaching.

“But, it has been recognised that programmes to be delivered partially or fully online, need to be developed with that mode of delivery in mind. This is opposed to merely being translated or transferred from the original face-to-face programme model.”

As many providers look to maintain online delivery of courses in the future, blended learning programmes need to be designed, delivered and assessed within an approved quality assurance framework developed by a provider. Consequently, QQI is working with DCU to enhance the current blended learning guidelines to incorporate fully online programmes. The NIDL team led by Professor Mark Brown and Dr Eamon Costello will research national and international best practice, conduct listening exercises with providers and other stakeholders and draft the guidelines.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a watershed moment for online learning in Ireland and around the globe. According to Mark…

“The development of these new guidelines provides an excellent opportunity to synthesise what the literature tells us about best practice and for the sector to share their own lessons to help shape future quality considerations.”

So we would encourage all Irish tertiary providers to join QQI and the NIDL team on the forthcoming listening exercises. Walter adds, “QQI will then organise formal consultation before finalising and publishing the guidelines. It is hoped to have the final version in early 2023.” Watch for more information shortly on the consultation process and listening workshops as we begin this exciting new initiative.

References

Mac Keogh, K. (1998). Effective partnerships in ODL: Implications of the Irish National Distance Education Centre Model, in Gooley, A. (ed) Open Learning ’98: Offering New Directions Brisbane: Queensland Open Learning Network pp. 31-36.